Bein’ with You This Way: One of the Hardest Parts of the Pandemic

I feel great sadness that—despite all the community building and positivity I could muster—the classroom did feel that way this year: alone together.

Share

June 15, 2021

I feel great sadness that—despite all the community building and positivity I could muster—the classroom did feel that way this year: alone together.

Share

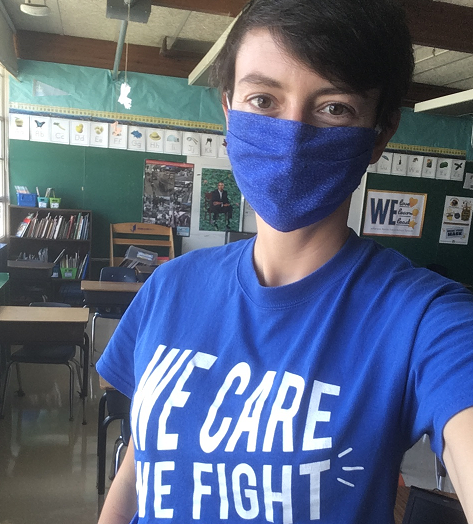

By Rosamund Looney

Alone Together

We fill the last day of first grade with a bonanza of art projects. We make paintings and then cut them up into collages a la Eric Carle. We draw final diagrams of our seedlings and pack them up for home. We go outside to make sun prints with leaves. Instead of the same reminders about personal space in the classroom, I point out the shadows that my students’ bodies are casting on the prints, and they quickly hustle sideways, saving our prints from shadowy obscurity. I am trying—impossibly—to squeeze every fun and free moment that we missed this year into our last day together. It feels strange and unusual. We stand around waiting for the patterns to emerge through the sun print paper; some students fall quickly into conversation, others stand silently, some pick at the grass. It feels like we’ve all lost a little of our sparkle and our spontaneity—our ability to be with each other easily, without care.

I think about a story from the famous children’s series Frog and Toad. The story ends with the line: “They were two close friends sitting alone together.” I feel great sadness that—despite all the community building and positivity I could muster—the classroom did feel that way this year: alone together.

The students’ physical and spatial awareness has been finely tuned during this pandemic year. In a normal year, 6-year-olds would learn to negotiate physical space together: with their friends in playtime, in partner reading, when dancing. We would normally have discussions on why you should choose to respect personal space so that you don’t make someone feel uncomfortable. This pandemic school year, personal space was mandatory, non-negotiable and enforced. All of us—children and adults—spent a lot of time monitoring other people’s bodies as they came close to our own.

My small students are able to articulate the impact of social distancing (unlike the many intangible effects of the pandemic) because it is so concrete. When I ask about the hardest part of the pandemic, a student tells me that it was having to “skip a seat.” His most profound loss was being close to his friends. I try to think of a positive spin. Will the children schooled during the pandemic be better at respecting boundaries and at consent, I wonder? Or in my stress to enforce safety and mandatory social distancing, was I unable to convey a larger message of why/how/for whom that would resonate beyond pandemic life?

I’m not sure what messages we will take with us as we shift into this new stage of the pandemic—one where we are supposed to slowly go back to normal. But what does normal mean now? For small children, essentially nothing has changed: They are still not vaccinated and won’t be eligible until the fall, at the earliest. I wonder about the vaccine rollout and how it will proceed in my district, the largest school district in Louisiana and one that primarily serves low-income children of color. I am concerned that families’ wariness of the healthcare system—due to immigration status, the political climate and systemic disparities in healthcare quality—will result in few students receiving the vaccine once they are eligible.

I am also doubtful that my district, which dropped its mask mandate as the school year ended, will require students or teachers to be vaccinated. As I reflect on this pandemic year and look to next school year, I wish I were able to celebrate a return to normal.

Instead, it feels like next school year will be a return to our pandemic normal, but less safe: an unmasked, partially vaccinated class of students who will or won’t be required to stay socially distant. We’ll be alone together in a different way.

As I began to think about the upcoming year, I found out that the district was planning infrastructure improvement plans for this summer; I attended a school board meeting to ask about the project happening at my school. They will be replacing my classroom’s 1950’s wall of windows with … fewer windows. I asked if the windows would still be operable; the board members stared at me, perplexed. The chief of operations jumped in: No, he apologized, the new windows will not open. But, he claimed, the idea that opening windows helps with ventilation during the pandemic is true up North, but not down here, in humid Louisiana. I was left dumbfounded and irate; this “upgrade” leaves the science behind. I want us to have fresh air in the classroom during and after the pandemic. We shouldn’t have to be together in a way that’s less safe.

Despite these frustrations, I keep up hope for us all to return eventually to a post-pandemic new normal, one where we remember the losses of the pandemic, and keep our appreciation for the things and people that we’ve been able to win back. May we— in school and in life—long appreciate physical closeness, collaborative work and unstructured social time.

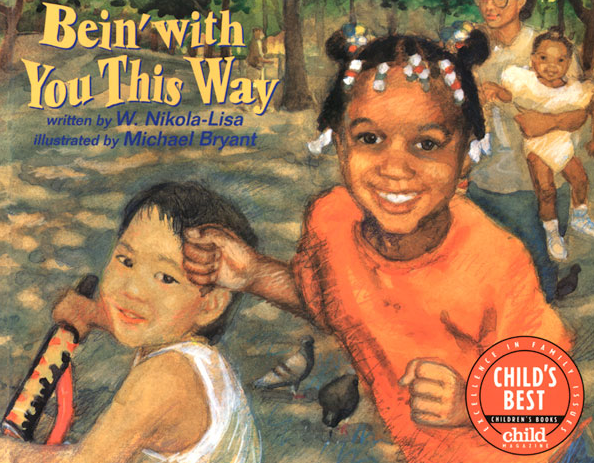

In class, I read the students a children’s book called Bein’ with You This Way, which celebrates various ways to spend time with people who appear different from you. The title matches this moment. We really were with each other this pandemic way: in a class with open windows and separated desks and partner work from a distance. As we wait to see when vaccinations for young children will roll out and how long schools will adhere to pandemic protocols around masking, distancing and quarantines, I wonder: What is our new way? How long will we be alone together?