Oral literacy, a foundational activity in a literacy classroom, can take a variety of formats. It might include speaking in a formal presentation, participating in a drama, or readers’ theater. But at its most basic level, oral literacy is simply conversation with a clear focus: to give students an opportunity to make meaning or to demonstrate their own understanding. I explained to my students that classroom conversations were simply on-task talk, and because students were really good at talking, they would be great when we had our conversations. It helped me set a focus and then allowed me to build on their conversational skills to move into more public and performance types of speaking.

Helping your students develop their oral literacy skills does not have to be difficult. After my first book, Classroom Motivation from A to Z, was published, I asked teachers which ideas were their favorites. I was surprised to discover that the most popular response was one of the simplest ideas: Give students a microphone. Erin Owens, a first-grade teacher, shared her story with me:

My students share a great deal. I have found that a microphone has played a key role in motivating them to produce quality work. First of all, they love the microphone; at first they say it is like “being on ‘American Idol.’” You can hear them more clearly and their voice is obviously amplified. This gains the attention of the audience more than traditional sharing. After the “glamor” wears off, they begin to realize that they are showcasing their work each time they step up to the microphone. I began to see a major change in their motivation to produce the best work they were capable of to impress and entertain their peers. Isn’t that the point—helping our students do their best?

Middle school teacher Katherine Ledford notes that by teaching students to talk, you are also teaching them to think critically:

Students have to be able to talk through a situation to consider it completely. They have to be willing to listen, share, and respond to and with each other. … Students [have] to think critically by talking through a situation first, then responding to it by connecting to their personal experiences and exploring the outcomes through conversations with their peers and me.

Ongoing Opportunities

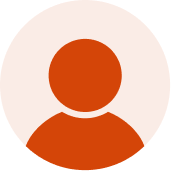

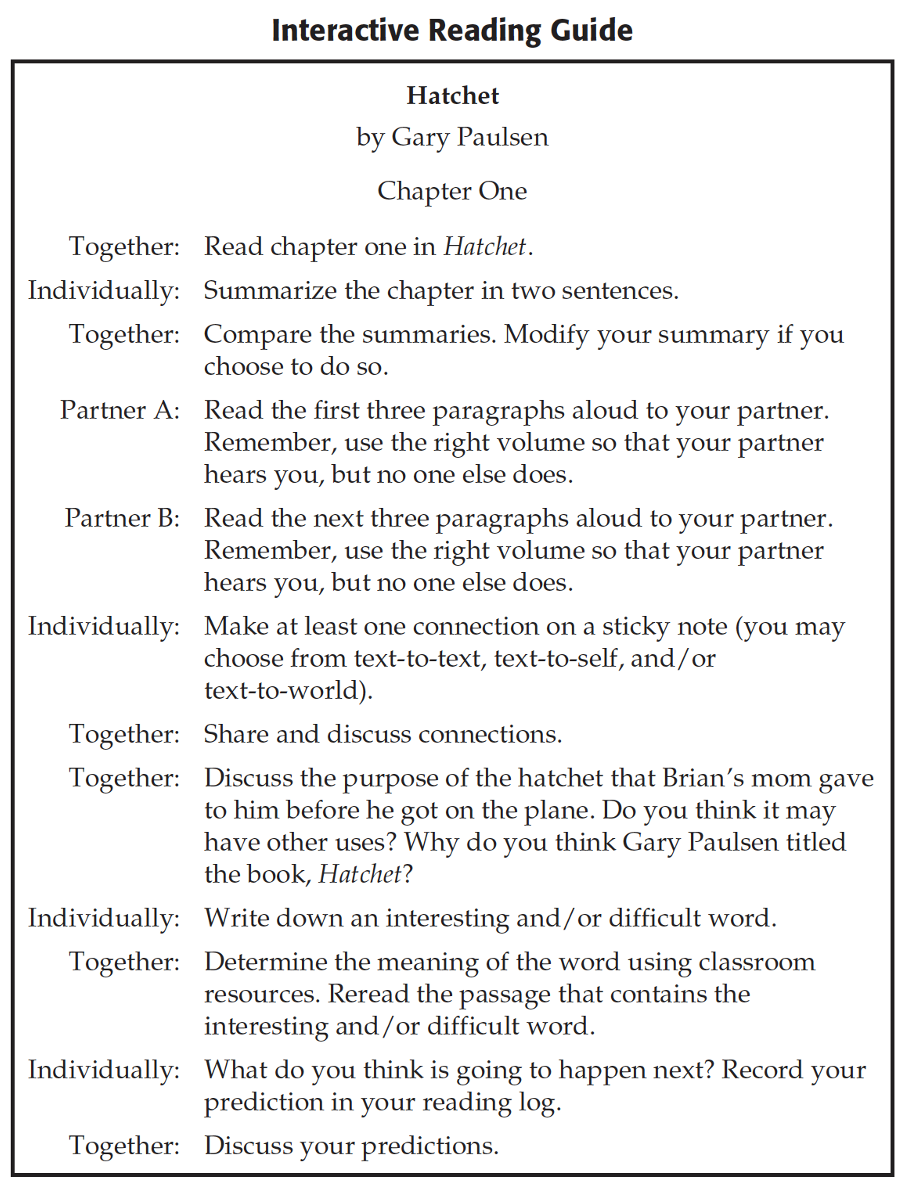

Think about your own classroom. There are probably plenty of times you can create options for your students to talk about learning. For example, I regularly visit classrooms where teachers use the Think-Pair-Share approach, asking students to think about an answer to a question, then pair up and share ideas. Or, the teachers ask students to form small groups and discuss what they have read. One effective teaching tool is an interactive reading guide, which balances independent student work with opportunities for discussion and oral reading.

Carie Hucks capitalizes on her middle school students’ desire to socialize: “I try to incorporate sharing into every lesson with my students. A trick I use is colored dice. I post questions specific to a lesson in the room and match the question with a number 1-6. I give each group of students a set of dice. They take turns rolling the dice and respond based on the number rolled. The novelty of being able to roll dice helps engage my students in the lesson more effectively than just giving them questions and asking them to discuss.”

Another fairly standard activity that involves on-task talk is asking students to create their own questions. Students can work in pairs or small groups and make up questions about a story they have read, or to review for a test. Especially at the beginning of the year, I found that my students struggled with the open-ended nature of that activity. It seemed they needed a bit more support, so I made sets of question starter cards. They could draw a card and use the starter word or phrase to create their own questions. That extra bit of support was very helpful. Then, as the year progressed, they were able to craft high-level questions without any prompting from me or the cards.

Literature Circles

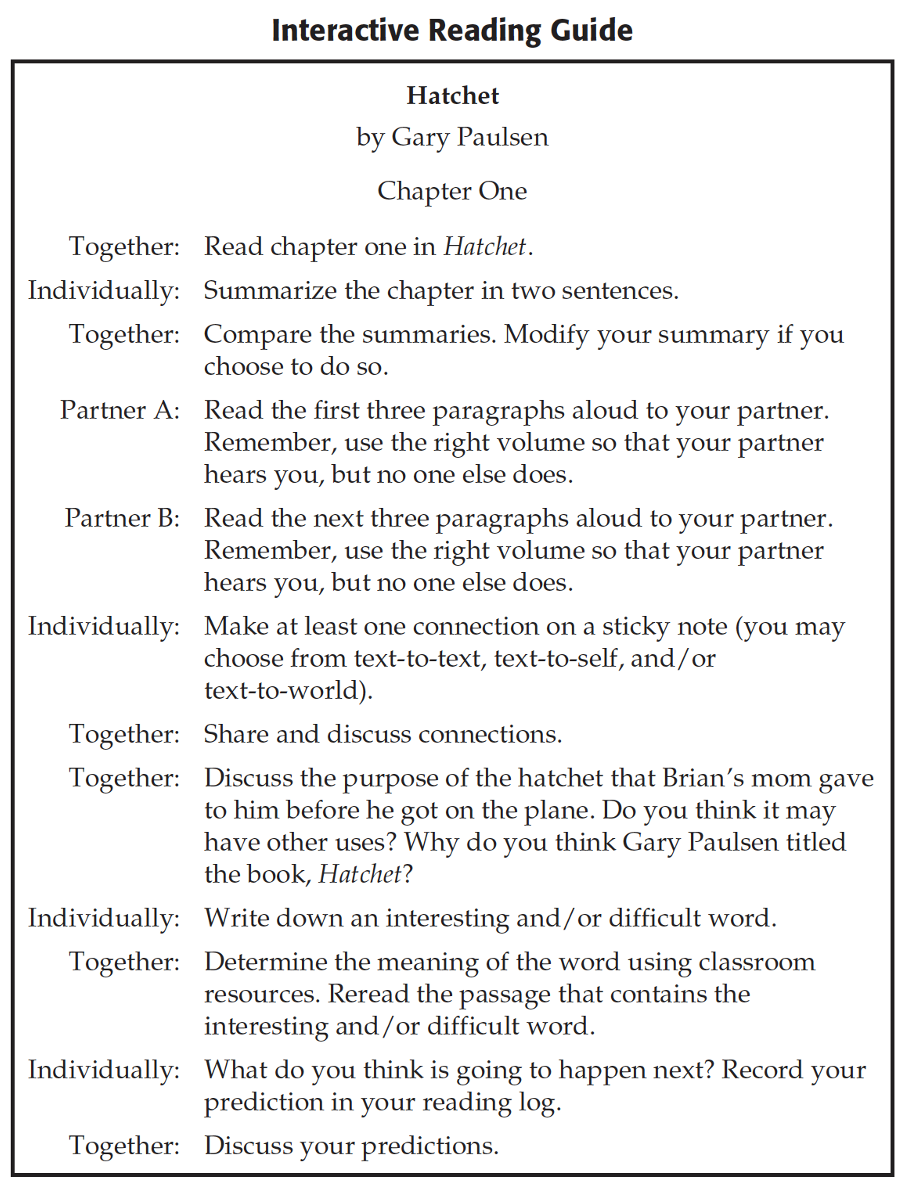

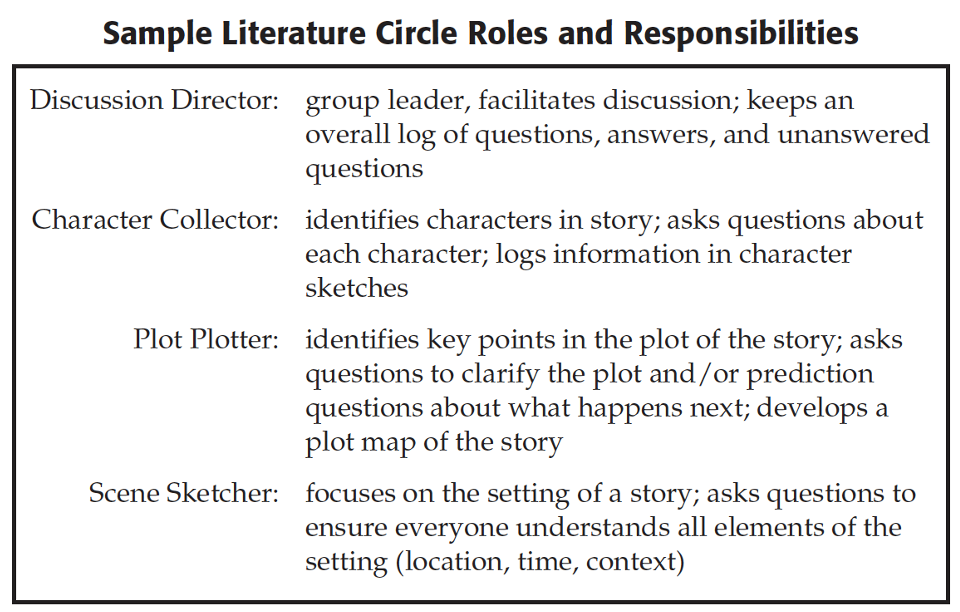

Elementary school teacher Amy Williams finds that literature circles are an effective option for student discussion. She points out that “each student has a role to complete and must use the tasks associated with the role to add to discussions of the book.” That is important; otherwise, one student may dominate the conversation, while others simply sit back and listen. When I was teaching, I assigned specific roles to my students and rotated those roles regularly. I also taught them how to effectively communicate their roles through conversation prior to literature circle activities.

Grand Conversations

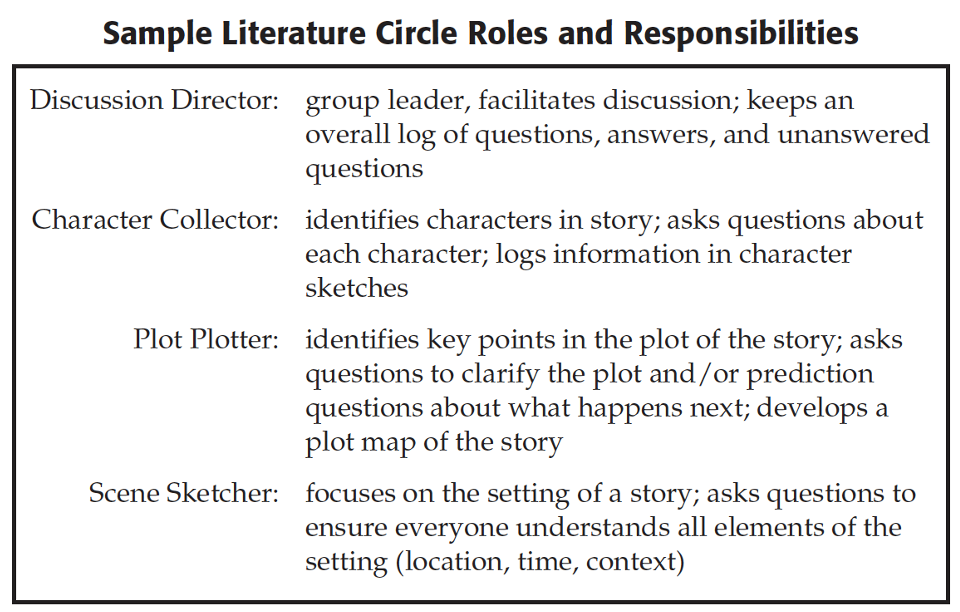

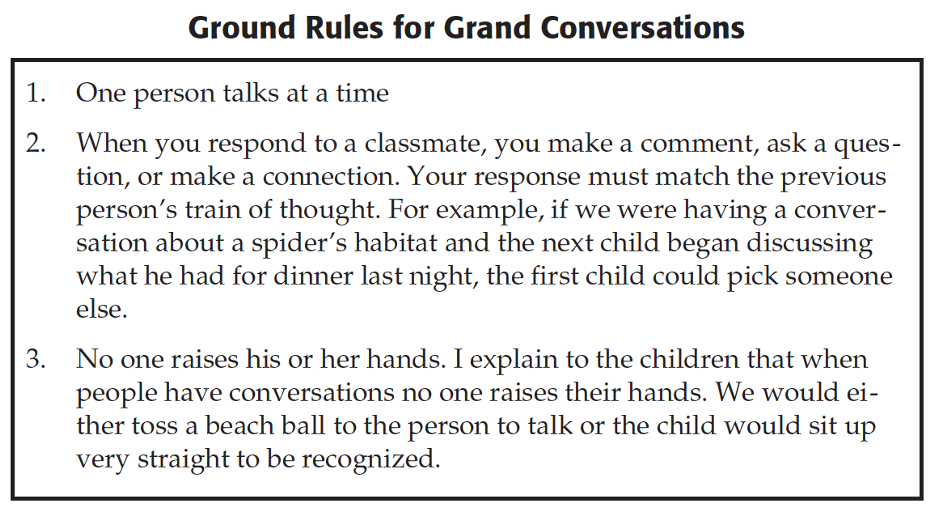

Connie Forrester describes one of her favorite kindergarten literacy activities, Grand Conversations:

I would usually introduce this strategy in October during our unit of study on nonfiction. To introduce the strategy, I would ask the children if they knew what the word ‘conversation’ meant. After some discussion, one child would usually come up with the fact that conversation is talking. I would go on to tell the children that Grand Conversations are one strategy that the big kids use when they talk about books. I would explain the ground rules to the children. You would be amazed how quickly the children catch on and how much they enjoy this strategy. They would beg to use it after we had read a book. However, I found Grand Conversations worked best when used after a nonfiction text.

Understanding What Good Looks Like

I think one of our challenges as teachers is helping our students understand what we expect of them. As a first-year teacher, I didn’t realize I needed to teach my students how to speak. After all, they talked constantly; why would I need to tell them how? But if we want students to grow in their oral literacy skills, we should teach them what to do, give them a variety of opportunities to practice, and allow them to assess themselves and each other.

Lindsay Yearta and I collaborated on a simple rubric to help her elementary students understand her expectations for speaking in class. This could also be done with your students as a way to help build ownership. She began by listing what she looks for as her students speak: whether they are on topic and speaking on levels that are appropriate for the audience or purpose, the level of their voices, and their confidence as speakers. We then created a simple criteria, using the acrostic SPEAK. Finally, we described what speakers look like when they are not doing enough, doing too much, or if they are just right.

A Final Note

Incorporating oral literacy in your classroom is critical. Using a variety of activities is enhanced by providing your students with clear guidelines for speaking.