The Principles of Democracy and Literature

Jess here—hi, all! I was recently invited to participate in a national event known as Writers Resist, which was sponsored by PEN America and intended to be a celebration of democracy by way of language. Many events featured both established and emerging writers who opted to read their own work as well as excerpts from a diverse group of respected American authors showcasing the best elements of democracy.

Before the event, I wondered how political it would be—having been organized after the presidential election. As a teacher, I worried a bit about how my participation might be interpreted. As a writer, I was absolutely compelled to be at the Burton Barr Library in Phoenix, one of three Writers Resist gatherings in Arizona that day.

As I began to prepare, it became clear to me that my love and reverence for teaching are inexorably linked to great literature, and such literature absolutely illuminates the principles of democracy. Language has the power to divide and to unite. It is the glue that binds cultures through documents, stories, poetry and song. Language can start wars, but also has the power to end them. These facets of language are what I most desire my students to consider, so I hoped being immersed in Writers Resist for the day would lead to new ideas for lessons.

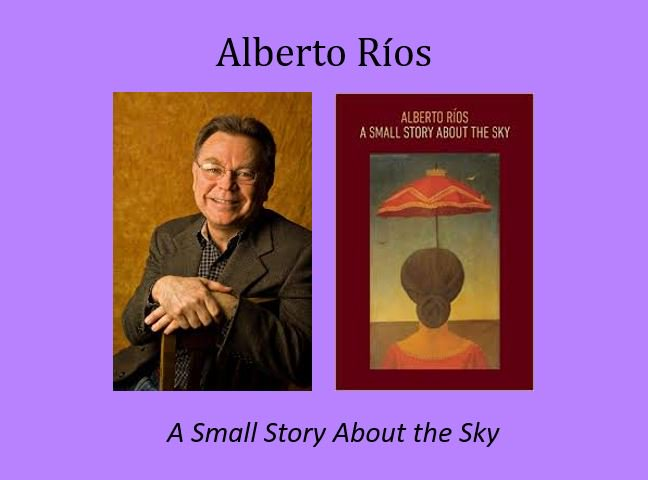

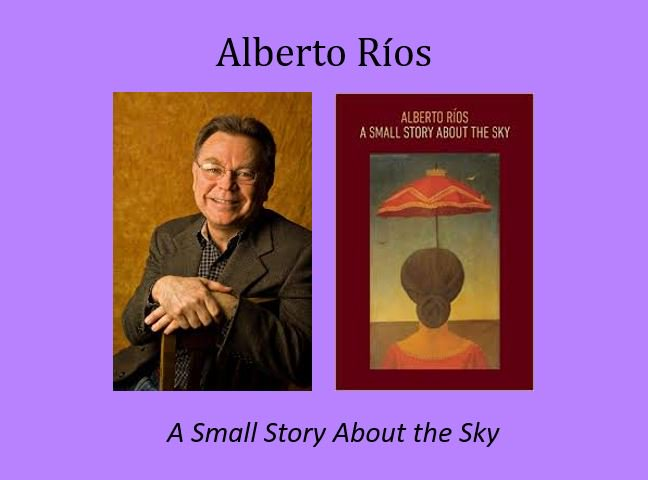

The event was a gorgeous synthesis of ideas, language and writers I hold dear. Professor Sally Ball, a poet at Arizona State University hosted the event, and the lineup was magnificent. Two state poet laureates were there, including former state laureate, Alberto Ríos, who often writes about the duplicity of identity and having grown up in a border town.

I love to study his poem When There Were Ghosts with my creative writing class during our unit on identity. You can find a wonderful lesson to accompany this poem here, at poets.org.

Choosing what to read that day was no small feat. Sally Ball encouraged us to read works by others, and I loved that idea. I spent several hours poring over works that I realized would also be wonderful to integrate into my English/AP/Creative Writing classroom: Langston Hughes, Emma Lazarus, Walt Whitman, Thomas Jefferson, Anne Bradstreet … the list goes on and on.

Ultimately, I chose two pieces. The first was Charlie Chaplin’s final speech from the film The Great Dictator, which has fantastic elements of satire-turned-earnest emotions in support of democracy. I can’t wait to show the clip to my sophomores when we study satire this spring.

There was standing room only on the day of the event—a cold and rainy day. The room was warm, the crowd was receptive, and each reader shed light on how language shapes and reflects the principles of democracy. While my focus was mostly on poetry, many read nonfiction and parts of fiction as well.

Which democracy-based texts most inspire you and your students? Be sure to comment below!

I left that day feeling energized and with an arm’s-length reading list I was eager to introduce to my sophomores and/or seniors. You can view the performances of the Phoenix Writers Resist here. I also couldn’t wait to hear from Tricia who attended the Writer’s Resist in New York City. It was magical knowing that my kindred spirit and co-author was experiencing this event on such a grand scale—how would Tricia view Writers Resist in tandem with her classroom and age group?

And from Tricia : If not for Jess, I would know nothing about Writers Resist! Luckily for me though, during one of our lengthy conversations about things that matter to us right now, she insisted that I get on the website to learn about the event planned for New York City. I did so immediately and was thrilled to see the names of some of my favorite authors who write for young adults listed as participants. That sealed the deal. On Jan. 17, I stood on the steps of the New York Public Library, with over 2,000 people, listening to authors read from their own work and the work of others in an act to defend freedom of expression.

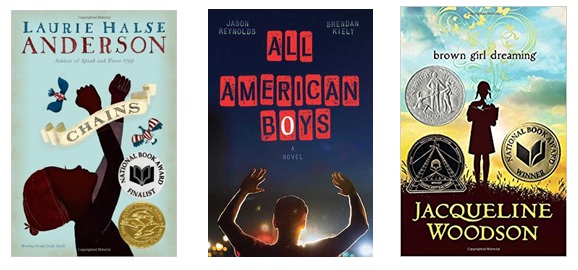

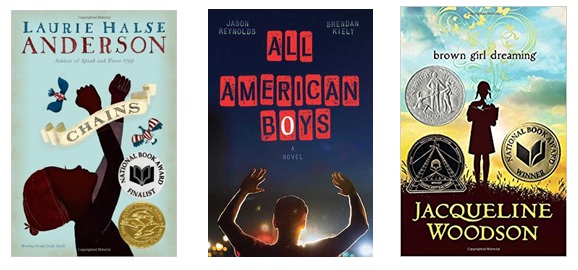

Laurie Halse Anderson. Jason Reynolds. Jacqueline Woodson. These are authors whose books I hand over to friends who are not in education to show the important work that is happening in young adult literature. They write books about issues that matter—to them and to the world. Books that confront and challenge the thinking of readers. Books that demand discussion and debate.

Anderson, Reynolds and Woodson are favorites of my students as well. I do not need to “book talk” their books; my eighth-graders take care of that for me. I struggle to keep these authors’ books on my shelves, and I regularly need to replace copies of texts that never make it back to my library, though I am pretty sure they are being read and reread.

Seeing the writers read at the Writers Resist event challenged me to consider how I might share this aspect of their work with my students. It brought me to think about how writers do resist all the time through the act of writing. As I type this, it seems like a simple idea, though it is one I have not yet highlighted with students directly.

When students read the works of Anderson, Reynolds, Woodson and countless others who take on important issues in their writing, I’d like them to consider these questions:

- What ideas/norms/traditions is this author resisting?

- How is he or she doing so? This is a powerful critical lens that students can use to analyze texts throughout their lives.

I’d also like to empower students as writers to learn how to use language as an act of resistance for causes they deem important. I want them to see how they can harness the power of words in various genres to make a statement, to provoke thinking and to enact change.

I strongly believe that in order for student writers to hear and respond to this call to action, they need to be provided with real-world reasons to write and authentic audiences for whom to write. NaNoWriMo, the Scholastic Art & Writing Awards, and the New York Times editorial contest provide three such opportunities.

The NaNoWriMo (short for National Novel Writing Month) young writers program challenges individuals to commit to write a 50,000-word novel during the month of November. The program engages writers who are 17 and under to set their own reasonable and appropriately challenging word-count goals. This past fall, my colleagues and I participated in this new adventure with our students, and we were amazed by their commitment, creativity and courage. I can envision providing young novelists with an additional invitation, asking them to consider how they might use fiction to challenge ideas, norms and traditions.

The Scholastic Art & Writing Awards program is an opportunity for student writers in grades 7-12 to submit work in a broad range of categories, including critical essay, humor, journalism, poetry and short story. The competition, which has run since 1923, accepts submissions each year starting in September and running through December.

The New York Times editorial contest calls on students to “write about an issue that matters to you.” This contest, which is open to students who are 13 to 19 years old, recently featured the winners of their seventh annual contest.

Do you know of other real-world, authentic opportunities for student writers? Please share by adding to this blog’s comments!

Great writing/instructional sites for all ages:

Poets.org: This site is sponsored by the Academy of American Poets. In addition to being able to browse for poems by subject/theme/occasion, you can also find an entire section devoted to materials for teachers. Don’t forget to sign up for the group’s Poem-a-Day as well.

Poetry 180: According to Billy Collins, a former U.S. poet laureate who hosts this site, “Poetry 180 is designed to make it easy for students to hear or read a poem on each of the 180 days of the school year. I have selected the poems you will find here with high school students in mind. They are intended to be listened to, and I suggest that all members of the school community be included as readers. A great time for the readings would be following the end of daily announcements over the public address system.

“Listening to poetry can encourage students and other learners to become members of the circle of readers for whom poetry is a vital source of pleasure. I hope Poetry 180 becomes an important and enriching part of the school day.”

Writing for Change at Teaching Tolerance: From the site: “Language is a paradoxical tool—we use it consciously to shape our thoughts and experiences, yet patterns and structures in the language itself can shape us in return. As this guide shows, American English frequently both reflects and reinforces systems of oppression in U.S. society.

“For example, a newspaper report describes a local event: ‘Over a thousand people attended with their wives and children.’ How does the statement relate to sexism and ageism? What does the statement communicate about who is a person and who is not?

“Teachers, students, trainers and others can use Writing for Change to expose bias in language. And—you can discover ways to communicate in more equitable terms. This guide offers more than 50 free, downloadable activities for personal or instructional use.”

Visual Writing Prompts. This is a wonderful sight rich with visual prompts for high school students.

Forward Thinking with Kindred Spirits:

Kindred Spirits will gather with you here twice a month to explore current human rights issues, to highlight useful resources, and to feature teachers and leaders who are pioneers of this important work. We aim to provide spark after spark of information and inspiration around this collaborative campfire in the hope that your participation will keep the spirit glowing.

Our next post will center on promoting civil discourse in the classroom, teaching students how to meaningfully discuss and debate issues and oppositional perspectives in a thoughtful, thought-provoking and considerate way.

Author Bios

Tricia Baldes

Tricia Baldes earned a master’s in English from Lehman College and has been a middle level educator since 2001. Her passion for human rights education has led to her writing curriculum and consulting with nonprofit organizations like Creative Visions, Speak Truth to Power and KidsRights. She co-authored the Rock Your World curriculum and currently works with the team as a program coordinator. In addition to presenting at national conferences for NCTE and ACSD, Baldes has led various teacher trainings and programs for students. She teaches eighth-grade English in Westchester County, N.Y.

Jess Burnquist

Jess Burnquist is the VP of Education and Youth Empowerment at Creative Visions. Her writing has appeared in the Washington Post, Time.com, NPR.org, and various online and print journals. She is a recipient of the Joan Frazier Memorial Award for the Arts at ASU and has been honored with a Sylvan Silver Apple Award. Her poetry chapbook You May Feel Your Way Past Me is available from Dancing Girl Press.

Explore more resources on the principles and foundations of democracy in our curated collection

Powerful writing and wonderful resources! I would add the Letters About Literature contest sponsored by the Library of Congress - http://read.gov/letters/. Their tagline says it all: "Read. Be Inspired. Write Back."