Does Money Matter in Education? Third Edition

New research confirms what educators have long known: adequate and equitable school funding directly improves student outcomes, while funding cuts cause harm—especially for underserved communities.

Share

February 28, 2025

New research confirms what educators have long known: adequate and equitable school funding directly improves student outcomes, while funding cuts cause harm—especially for underserved communities.

Share

By Bruce D. Baker and David Knight

In the previous edition of this report (published in 2016), we reviewed the evidence on whether money matters for the performance of K-12 public schools. Our conclusion, which was entirely unsurprising to educators, was that the research overwhelmingly suggested that adequate and equitable school funding is a necessary precondition for improving student outcomes.

Some of these earlier studies, however, relied on insufficient data and methods, and they sometimes reached inconsistent conclusions. This led to confusion about and misrepresentation of what the research said.

Since then, a steady stream of new studies, using even better data and more advanced statistical methods, have been published. In this updated edition, we review this newer evidence. We find, put simply, that it has not only settled the question of whether money matters (it does), but has also let new light shine through on key details, including the kinds of investments that matter, who benefits most from them, and the impressive magnitude and consistency of their impact.

In this report, we provide a comprehensive review of the research on the effect of K-12 school funding on student outcomes. In other words, does money matter in education?

This is the third edition of this review, with the first two editions having been published in 2012 and 2016. When those previous reports were released, the nation’s schools were still in the extended wake of the 2007-09 recession. School districts in virtually all states had been hammered by cuts, with the damage being particularly severe in higher-poverty districts and those serving larger shares of Black and Hispanic students. The impact of these cuts persists even today.

This erosion of investment in public schooling was, to be sure, a result of a catastrophic recession and the collapse of the housing market that accompanied it, but the draconian cuts were also justified in part by common arguments that more money wouldn’t improve schools and student outcomes. Indeed, some went as far as to argue that the cuts would be beneficial, as they would force districts to be more efficient and achieve more with less. As we showed in our first two reports, such arguments were, at best, baseless claims contradicted by the empirical evidence at the time.

Today, a full eight years since the second edition of this report, the state of the “does money matter?” debate has improved in some respects, but not in others. On the positive side, a consistent flow of recent analyses, using better data and more sophisticated methods, has confirmed and elaborated on decades of prior research on the importance of adequate and equitable funding in K-12 schools. To whatever extent the idea that “money doesn’t matter” was ever credible, it is no longer.

On the other hand, this emerging consensus that money does, in fact, matter is not yet reflected in many—perhaps most—states’ K-12 school finance systems and policymaking. There is also persistent confusion on many of the critical issues underlying the general “money matters” conclusion. Such confusion is understandable. The research literature on the impact of school spending, both before and after the publication of our last report, is large and complex. It includes studies of whether additional K-12 spending improves outcomes (and whether less spending hurts outcomes), but it also includes dozens of analyses of how this impact varies between locations and student subgroups, as well as studies of the impact (and cost effectiveness) of individual policies on which education dollars are or might be spent.

In this report, we provide a fair survey of this school finance research landscape, one that we hope will inform and improve debates and policy. The body of this report offers a great deal of nuanced discussion of studies that may serve in this capacity, but our primary conclusions are summarized below.

The overwhelming bulk of studies we review show that infusions of additional money into schools lead to improved student academic achievement and outcomes later in life, while a handful of studies also validate that funding cuts, resulting from major events like the 2007-09 recession, lead to a decline in student outcomes.

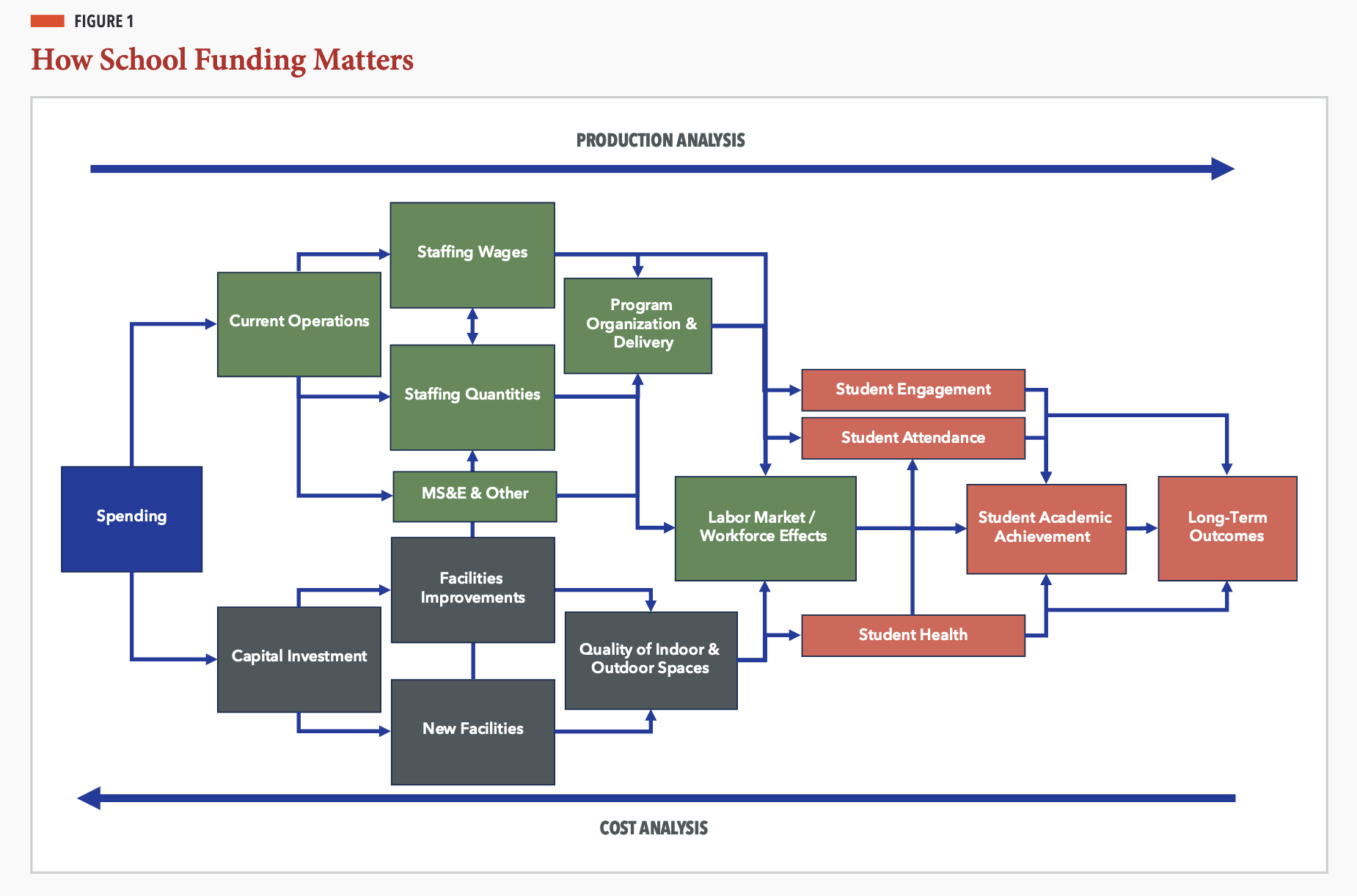

The largest share of annual operating spending in public schooling goes toward (a) the competitiveness of teacher and other school staff wages; and (b) the quantities of school staff that can be hired. In other words, it goes to paying teachers more and/or hiring more teachers. Both matter, and a high-quality public schooling system requires a “both/and approach,” rather than an “either/or approach.” Competitive wages are needed to maintain or improve the quality of the teacher workforce, as such quality matters for student outcomes. Reduced class sizes and staffing ratios (including tutoring) also lead to better student outcomes in the short or long term. On the capital investment side, spending on school facilities also improves student outcomes, both directly (e.g., providing healthy and safe spaces for student learning) and indirectly (e.g., supporting teacher recruitment and retention by offering high-quality, productive workspaces). For instance, improvements to heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems offer a relatively large return on student achievement outcomes. Generally, investments in capital have a four- to six-year lag between the commitment of new funding and measurable positive effects on students.

Several studies discussed herein validate that spending more on schools and communities that have previously been deprived of resources yields greater returns on investment than spending where prior investment has been high and student need relatively lower; the difference in return on investment may be as high as 20-fold. These findings validate the importance of promoting funding progressiveness in state school finance systems, with the goal of equal educational opportunity for all.

Whereas school finance legislation and litigation receive the most attention, the reality is that changes in the amount and distribution of school dollars can occur due to a variety of reasons, including:

Multiple causal studies discussed herein validate that, whatever the cause of substantive changes in school funding, those substantive changes matter. They influence student outcomes. Many multistate studies broadly characterize school finance reforms, often as a collection of judicial pressures and legislative responses, on balance finding that those reforms lead to positive outcomes for children. Others focus on economic fluctuations, finding that, when economic shifts lead to changes in school funding, those changes also matter for student outcomes; increases help and cuts hurt. Still others focus on local referenda leading to investment in capital infrastructure, or specific features of school funding formulas that drive additional funding to individual school districts or protect them from losses; once again, these changes affect outcomes. Regardless of the cause, the research shows that increased funding improves student outcomes and that decreased funding harms student outcomes.

To learn more, access the full report here.

Access 35+ free, one-hour professional development webinars—anytime, anywhere. Explore the topics that matter most to you, earn PD credit, and grow your skills at your own pace.

Want to see more stories like this one? Subscribe to the SML e-newsletter!